Waves of Purpose, Tides of Change | Rev. Dr. Daniel Kanter | 09.10.23

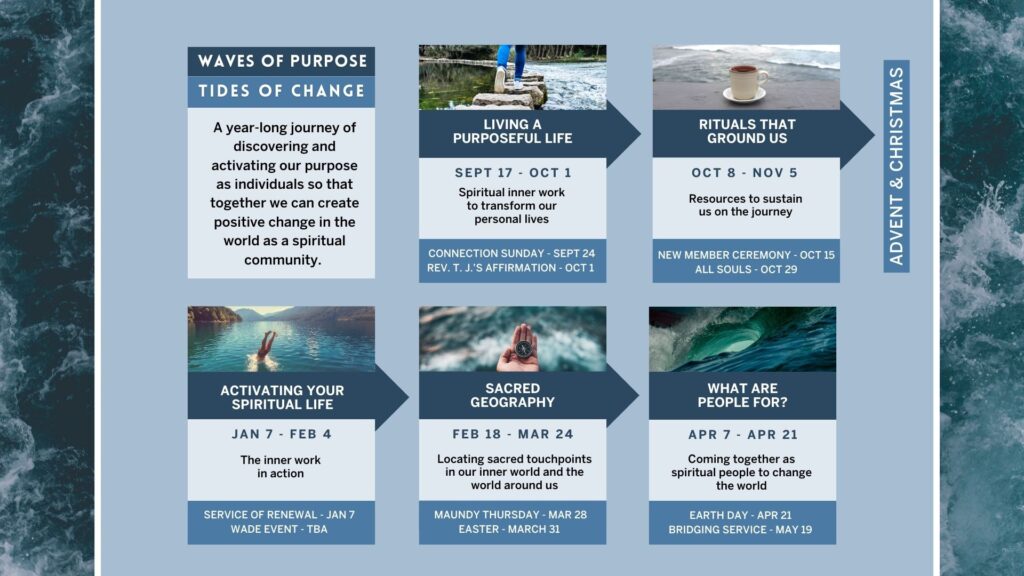

In this sermon, Rev. Daniel Kanter kicks off our ’23-24 theme year “Waves of Purpose, Tides of Change”: A year-long journey of discovering and activating our purpose as individuals so that together we can create positive change in the world as a spiritual community.

Throughout the year we’ll be exploring questions like:

![]() What does living with purpose really mean for a Unitarian Universalist?

What does living with purpose really mean for a Unitarian Universalist?

![]() What does grounding ourselves in rituals and activating our spiritual lives look like?

What does grounding ourselves in rituals and activating our spiritual lives look like?

![]() Where do we find resources to grow and guide our actions as UUs to make the world a better place?

Where do we find resources to grow and guide our actions as UUs to make the world a better place?

Sermon Transcript

In the beginning, God created the earth and he looked upon it in his cosmic loneliness and God said, “Let us make living creatures out of mud, so the mud can see what we have done.” And God created every living creature that now moveth, and one was man. Mud as man alone could speak. God leaned close to mud as man sat up, looked around, and spoke. Man blinked. “What is the purpose of all this,” he asked politely. “Everything must have a purpose,” asked God. I wish I could do that with my more Jewish grandfather. Everything must have a purpose,” asked God. “Certainly,” said man. “Then I leave it to you to think of one for all this,” said God and he went away.

Unitarian atheist banned book author Kurt Vonnegut wrote this little genesis story. It’s a feature in his book, Cat’s Cradle, in which the religion of Bokononism which is irreverent, nihilistic, cynical observational about life and God’s will with an emphasis on coincidence and serendipity has its founder as part of a utopian project to give people purpose and community in the face of the island’s unsolvable poverty and squalor. Some might say that the roots of every religion is this question, what is the purpose of humanity? Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Bokononism and Unitarian Universalism, religious history is rife with the question, what is our human purpose? Ever since we stood up in the plains of the Serengeti and looked out at the waving grasslands and fruit trees and saw the lions trying to eat us, we asked the question, what is our purpose? In those simpler times, we may have easily answered, to eat, to survive, so we did.

We went hither and thither in search of food and shelter and company, and it wasn’t always peace and tranquility. Yuval Harari and his magnificent book, Sapiens, says it very clearly, “Don’t believe,” he says. “Don’t believe tree-huggers who claim that our ancestors lived in harmony with nature. Long before the Industrial Revolution, Homo sapiens held the record among all organisms for driving the most plant and animal species to their extinction. We have the dubious distinction of being the deadliest species in the annals of biology,” he says. And rather flippantly, he also says, “Humans are the outcome of blind evolutionary processes that operate without goal or purpose. Our actions are not part of some divine cosmic plan, and if the planet earth were to blow up tomorrow morning, the universe would probably keep going about its business as usual.” “As far as we can tell at this point,” he said, “human subjectivity would not be missed. Hence any meaning that people inscribe to their lives is just a delusion,” Harari says, to which I nod.

I get it. I can get so cosmic in my thinking that I figure not much of anything we do matters if I think so far out into the cosmic future, that we created everything we know from money to morals, and if we strip away the basic things like food and we lock the doors, we might get quite challenged in keeping a civil society in this room. But I also believe that we do have purpose. If there isn’t some purpose for the end of the universe, it’s good enough to figure out what the purpose of our time and place is. History tells us that we have been pursuing this question from the time we stood up out of the mud, so why stop now? We fought for land and hunting grounds long before there were national and local borders. We wandered the earth. We buried our loved ones. We birthed miracles into the world long before we understood how it worked. We looked up at the stars and wondered what miracle made us and gave us the chance to stand there in the dark.

Our UU Ancestors Search for Purpose

And we had to make sense and create purpose that guided our actions as we held our fragile, frightened hands in dark caves as the fires went out, and those purposes shaped through human history, shaped over time, have shaped into religions and nations, and sometimes nation religions and sometimes religious nations, and sometimes to the detriment of anyone who wouldn’t go along with the state religion like our religious ancestors who said no to the Christian powers, that they didn’t last long. They didn’t sustain our communities. Our people asked, what is the purpose if it’s not the one handed down to us by the state or by the cathedral?

Our religious ancestors said, “No, Jesus was not God,” that it didn’t make sense that we worshiped and followed a God. “How could they follow God,” they said. We must have had to have a man at the center of what we followed, someone close to God, someone enlightened maybe. So, they said, “No, his death did not save us. The cross was violence by the state. His message of love, an example of lifting up those who struggled is the only thing worth pursuing and imitating,” our religious ancestors said. They said, “If we don’t then need atonement, it’s because we are good deep down. We are not sinners. And if God is a loving God and loves all, then our purpose is to extend love in all directions.” They even said that, “No, we don’t even know what God wants.” They said, “People who tell you they know exactly what God wants are fooling themselves, that God is too big to be put in a book or a box or inside a church.” So, they wrestled with their purpose and they passed down to us both questions and answers that came from this wrestling.

As one version of the Christian story was being forged into armies of the empire and disseminated through cathedrals and laws, our people said, “No.” They said, “Dissent is a worthy tool in society because it keeps us in a conversation of what is good for all of us.” They said, “No, some people aren’t better because they had the fortune to be born in the palace up on the hill, rather down and down on the farm in the valley.” They said, “No, we aren’t different because some of us had our skin darkened against the powerful sun or because our bodies happened to carry the birth of babies.”

So, they created a religion around these ideas, these ideas that were forged in forests in the middle of the 1500s in Poland and Transylvania and eventually on the town squares of New England, and they became us. And the purposes they created out of the many experiences of their lives, their disappointments and their struggles and their joys and their celebrations stated to be the most important thing to them was that we must be free, and to be free, we had to work at it. We couldn’t sit back and wait for God or a king to save us. We had to exercise our minds and our hearts and our souls to be in dialogue with each other and discern what is of importance and to make changes in ourselves and in our communities to what they would say, would be to create the kingdom of God here on earth.

Carrying the UU Tradition Forward

The humans who created this faith and this church did their best to say to us, “It matters that you confront those forces that neglect your very being.” “It matters,” they would say to us, “that when your state outlaws abortion for all women and then allows a frantic fringe of society to start talking about making it illegal to travel on the free roads to get abortion care, that we say, ‘come and get us because we aren’t going to stop helping people make choices about their bodies.'” Our ancestors would say to us through the purposes they created that it matters that ideologies that want us to give rights to fetuses over real live women who are standing before us are challenged, those ideas that carve out rights for something that is just potential.

Our ancestors would say, “You keep going. You keep building a center that helps women make their own choices.” And that’s what we’re doing. And it matters that when they say books are dangerous and should be taken off our library shelves that we in this church create a library with a big red sign on the shelf that says, “This is for banned books. Go up there and go look at it.” And it matters that when politicians say we are ending the education of black history in our schools and banning sex ed, that we teach racial equity and comprehensive sex ed. It matters that the answers to the purpose of humanity are churned over and rethought. And then, we still commit to dissent and to the value of every human being from a religious perspective that we call this living tradition because if we don’t, who will? That’s what we’re up to this year. We are exploring what the waves of purpose have done throughout our lives and in this church to create tides of change. It is both a personal and a communal response to the times we live in in this world.

Now, I went looking for inspiration and I found an obvious one, which was Reverend Rick Warren‘s book, The Purpose Driven Life, from the Saddleback Church, an Evangelical Church in Southern California. I heard just earlier that they were kicked out of the Southern Baptist Convention for ordaining women. How far behind is that? We’ve been ordaining women since the late 1800s. You’re all out of whack with that clapping, so just… The book, The Purpose Driven Life, sold over 50 million copies and was translated into 85 languages, so I decided to translate it into Unitarian Universalists. Here’s my summary, The Purpose Driven Life and what it means for us, this is what it is in four easy things. It is one, you matter, and two, helping others understand who you are and what your faith is matters. And three, listen to your inner voice when it wants to lead you to what is right, that matters. And four, serving others makes a difference. That’s all. You don’t have to read the book. You just got it.

In fact, 200 years ago, our Unitarian sage, Ralph Waldo Emerson, said this summary in one sentence. He said, “The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well.” Over my time as a minister these last 25 years, I have noticed this about people who live with purpose. I have noticed that they are located in a place they know how to commit to an idea of community, and I have noticed that they also assume responsibility, rather than expect others to fix things. And they often use the phrase, radical hospitality, to describe a philosophy in life that no one should be shut out of a [inaudible 00:15:06]. And I’ve noticed that people who live with purpose give themselves away and don’t want to be heroes for what they do, and I have noticed that they are part of a struggle to make life better, so they believe in a sense of radical mutuality.

Living with Purpose

Waves of purpose create tides of change, friends. So, we are asking you this year, what does living with purpose really mean for you and for you as a Unitarian Universalist? What does grounding yourself in rituals and activating your spiritual life look like? Where do you find the resources to grow and guide your actions as Unitarian Universalists to make the world a better place? We have planned a whole year to explore with you and we hope that you plan on being here. It looks something like this, and we’re going to print this out for you next week. It is to say that we have planned this. We don’t believe in monthly themes that come and go. We believe in a yearlong exploration that guides us through these questions, what it means to have purpose in our lives. It should all lead to a deeper sense of who you are, what commitments to things like activated dissent and radical mutuality are growing in you.

And we do this knowing that we can’t just focus our lives every minute and every day on being purpose-driven. That’s exhausting. We know that there are high tides and low tides, as the poet UU minister Elizabeth Tarbox said in the reading that my colleagues read to you. In that reading she concludes, “There is a time for high tide, being involved, and active, and taking risks, and putting our effort to master the elements, and there is a time for low tide, inactivity, quiet reflection, and both are necessary in our lives.” “May this be a low tide time for you when you can hear the voice of your own calming and thoughtful inspiration,” she says, “a time when thoughts come uncalled for to comfort and challenge you. And may you go from that renewal ready to answer the call of your destiny, to jump back into the tide of life once more.”

This year, friends, should be a time for both, for the activation and for the rest, for the reflection, for the dissent, for the commitment, for your hope, and for your focus on what you love and what loves you, and it should be a time when we reflect on how we participate in radical mutuality. The waves and the tides come and go in never ending movements of the world, so may we find a place in them this year together, in love with this holy world once again in step with each other and our deepest urges with our muddy selves asking important questions of each other and of the soul. Let’s begin. Amen.